Note: This interview originally appeared on Book Riot on February 13, 2014.

This past year was the 15th anniversary of McSweeney’s, the publishing force that Slate called “the first bona fide literary movement in decades.” To mark the occasion, they released The Best of McSweeney’s, a collection of highlights from their fifteen year run.

However, another book they released this past year, Crabtree (through their fledgling children’s arm McMullens), is perhaps an even better tribute to the iconic McSweeney’s style.

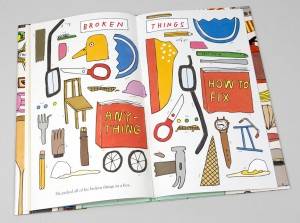

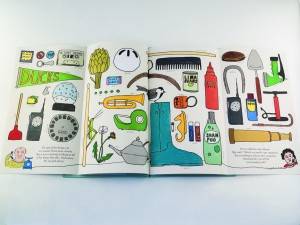

Having lost his false teeth, Alfred Crabtree starts to unpack and catalog his many possessions (whether he is a collector or a hoarder is up to interpretation). Starting with this very simple premise, Crabtree reveals itself to be a light-hearted meditation on how we are defined by our possessions.

It’s a good stand-in for the complete McSweeney’s oeuvre because like most McSweeney’s offerings, Crabtree trains a keenly observant eye on the unexamined life, uncovering quirky yet meaningful details that might otherwise escape notice. And of course, it is delivered with McSweeney’s trademark stylistic flair (as evidenced by the book jacket which unfolds into a full sized poster).

I recently had a chance to catch up with authors/illustrators/brothers Jon and Tucker Nichols and discussed (among other things) their process behind Crabtree, methods of delivering French cheese, and of course: glittery ponies.

(Note: All photos courtesy of Pat Castaldo, buyolympia.com)

Minh: This is your first children’s book. What is your professional background and what made you want to write a picture book?

Tucker: We really have no business writing kids’ books. But now that I say that I’m not really sure who does. There are probably degrees to be earned, maybe licenses even, but we have neither. We are brothers who draw whenever we’re near pen and paper. We really never stopped doodling since we were kids.

Jon: We are also now fathers who read books to our daughters.

T: Right. You can try to wriggle your way out of it, but if you have kids you will no doubt be forced to read a lot of really bad kids’ books to your children, so there’s a lot of motivation right there. We were lucky enough to be invited in by McSweeney’s McMullens to try our hand at making a book for kids. Prior to that, we really didn’t have a plan to make a book for kids. We would have probably just kept trying to hide the glittery pony books and reaching for the classics. That said, I’m so glad we did this. It’s been really fun.

M: How did the process of writing/illustrating a book differ from the other creative work you’ve done?

T: Jon is a musician so he’s a bit more used to collaboration. I’m a fine artist, and collaboration doesn’t come as naturally to me, at least with other artists. But Jon and I have been collaborating all our lives in one way or another, so this was different. We found our natural roles pretty quickly: Jon drew all the people and wrote most of the words. I draw all of the objects.

J: There are a lot of objects. I got off easy.

T: We both talked about who this guy Crabtree is, and how he thought about all of his things. And because so many of his things happen to be things we grew up with, the book ended up being surprisingly autobiographical. And then Brian McMullen somehow stitched it all together into a real book. Without him these would still be just a pile of seemingly unrelated drawings in my studio.

M: Is this your first official collaboration as brothers? And are you still on speaking terms?

T: Tell Jon he is welcome to answer this one first.

M: Tucker says you—

J: —I heard him. Yes, we work pretty well together. In terms of the actual work, we’re very much on the same page. I think the hardest part of collaborating is synching up schedules. There was a lot to hash out in this book, a lot to revise and rethink and decide about. And because we didn’t make the thing with the kind of absolute separation of author and illustrator that is more traditional in the making of kid’s books, we were kind of at the mercy of each others’ availability throughout the process.

M: There is a lot to dig into with these illustrations–what is one small detail that you would want to make sure readers don’t miss?

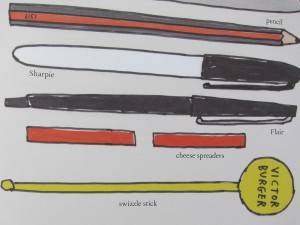

J: We’re currently in the process of translating Crabtree into French and one of the details we’ll have to lose in the French edition is a pair of rectangular plastic “Cheese Spreaders” on the Tools and Utensils page. Apparently, the French have ideas about cheese that don’t center around Kraft Handisnacks.

T: I’m super fond of the character “Nut” who appears in the family portraits, and then as a mayoral candidate in the front endpapers, and as a wanted man on the back endpapers. I’m hoping we haven’t seen the last of him.

M: You are both parents of young children and in another interview you mention the particular challenge of reading the same book over and over again (something we have all run into at some point). How did this guide your work on Crabtree and what makes this book different?

T: Most of it is just answering a simple question: can I picture reading this book out loud a thousand times without wanting to throw the lamp out the window? With Crabtree we are taking the path of trying to make a book that has so many different connective pathways that each time you open it you might have a slightly different experience with your child. It has a story, there are lots of things to look at, there are things to talk about with your kid, and some of it is just unexplainable. We also wanted to include the parents in the audience. So we’re casting a very wide net in the interest of keeping the lamp on the table.

J: Lamps are costly. But seriously, there are a whole bunch of ways to make a book that isn’t depleted after a reading or two. The hardest is keeping it simple and elemental. Poetic. I am a Bunny or Frog and Toad. Arnold Lobel’s books will always be on my shelves because they manage to tap into something that is the very essence of friendship, and friendship is at the heart of our humanity. Those stories are distillations. Crabtree takes a different tack and throws a lot of stuff at the reader. It’s more of a cornucopia, like Cars and Trucks and Things That Go.

T: And The Muppet Show, plus Gilligan’s Island, and a volume of some obscure encyclopedia from 1977. It’s not exactly spare.

J: That’s important though. My daughter’s six now, and she likes to go through random catalogs from our recycling bin and circle the things that interest her. It turns out, almost everything interests her when she turns her attention to it.

M: In the book, Alfred is searching for his missing false teeth. As an amateur psychologist (and avid-googler), I’ve read that dreams about losing one’s teeth are tied to anxiety around times of change or upheaval… which seems somehow fitting for Alfred Crabtree. Was this intentional or am I overthinking things?

J: I have those dreams! In fact the writing of this book, not coincidentally, corresponded with a lot of real-life periodontal nastiness for me. To the point where the dentistry tools we have in the book always make me a little uneasy. Yes, there is something profoundly elemental about teeth. I think we settled on the idea because there was an aspect to it that was a little bit vaudeville — denture gags not being quite as prevalent as they once were. But the losing of teeth is one of the things that late-middle-aged folks like Alfred and his young fans have in common. Teeth are bizarre and fascinating things. Imagine if we had other body parts like them — a set of adult eyes hanging out behind our kid eyes that would emerge when we turned five!

T: I’m ready for my adult eyes—that sounds great.

J: I just got mine. I’m afraid they’re called “progressive lenses.”

M: Who are some of your influences? (Not just limited to children’s authors.)

T: OK, here’s a list of decidedly NOT kids’ authors, truly off the top of my head: Michael Ondaatje, Lynda Barry, Cormac McCarthy, Lee Friedlander, William Eggelston, Alexander Calder, Billie Holiday, Tom Sachs, Denis Johnson, Jan Johannson, Etta James…wait I think I’m just listing things I like. Actual influences for me are probably closer to our mom, California, Saul Steinberg, Edward Gorey, our friends.

J: Tucker, you just put Cormac McCarthy in a list of your influences for a kids’ book. That’s perverse. I’ll mention Valeri Gorbachev, who is neck-and-neck for me with Richard Scarry for beautifully rendered anthropomorphic animals. I also love Rodney Alan Greenblat’s Aunt Ippy and Uncle Wizmo books , anything at all by William Steig, Roald Dahl, Richard Hefter, and the Oulipo writers, who wrote kids’ books for grown ups.

T: Way to take the higher ground. You’re making me look bad.

M: Do you guys have future book plans?

T: Yes.

J: Yup.

M: Let me guess… Crabtree and the Glittery Pony?

T: You never know with that guy.

J: Ha! As long as it has a tie-in to a major fast food franchise, we’re happy.

2 comments:

I simply could not go away your web site prior to suggesting that I extremely enjoyed the standard info a person supply for your guests?

Is gonna be back ceaselessly in order to check out new posts 온라인경마

When someone writes an post he/she retains the plan of a user in his/her brain that how a user can understand it.

So that’s why this post is perfect. Thanks! 카지노사이트

Post a Comment